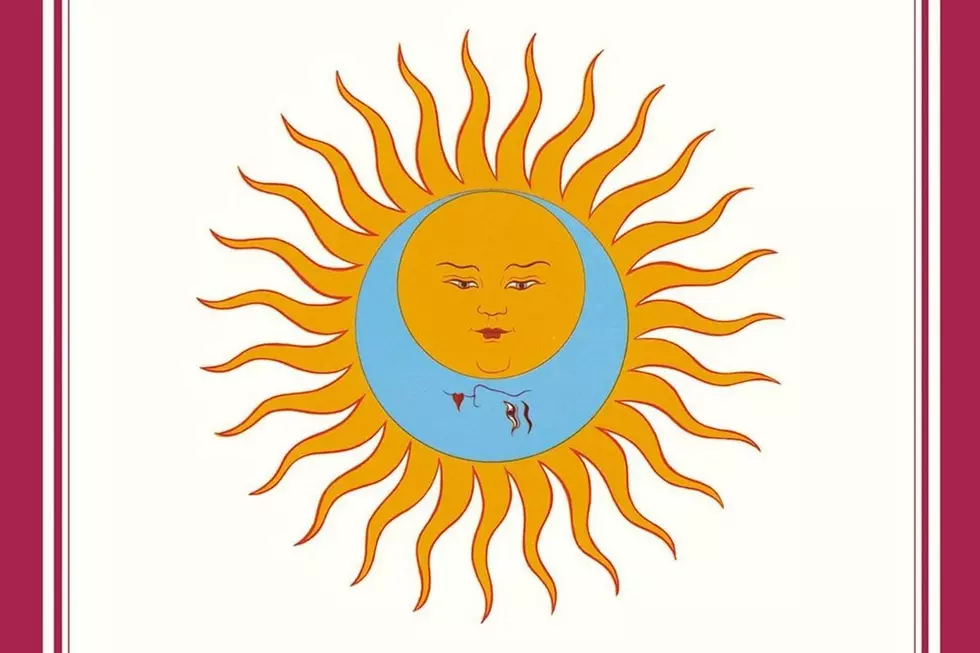

How King Crimson Reached a Prog-Rock Pinnacle With ‘Larks’ Tongues in Aspic’

King Crimson's fifth album, 1973's Larks' Tongues in Aspic, is a pinnacle of progressive rock, even though its music is nearly unclassifiable. It remains a genre unto itself – a mishmash of heavy and soothing, beautiful and unsettling, experimental and melodic.

Released on March 23, 1973, Larks' Tongues in Aspic is King Crimson's second classic album. With 1969's groundbreaking In the Court of the Crimson King, the band basically invented progressive rock entirely, utilizing bandleader Robert Fripp's epic approach to song construction, which layered aggressive fretwork with propulsive rhythms, jazzy woodwinds and the most iconic Mellotron sound ever laid to tape.

But just as soon as King Crimson birthed an exciting new musical movement, they retreated to the shadows. The band's following trio of albums (1970's In the Wake of Poseidon, 1970's Lizard and Islands in 1971) were scattered with brilliance, but mostly just ... scattered, as Fripp was unable to maintain a consistent lineup of players from one release to another (or even track to track).

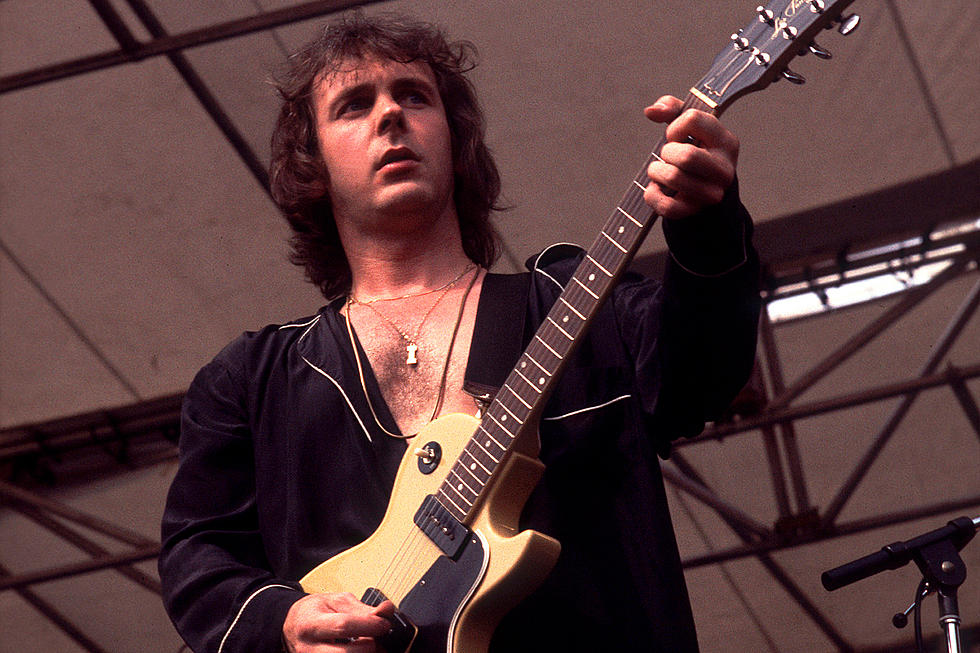

That pattern ended in 1972, when Fripp started recruiting a brand new lineup – one designed for an edgier, more unpredictable style of playing. He brought in two new drummers, designed to represent polar opposite ends of the percussive spectrum: Jamie Muir (an explosive percussionist with an unconventional approach and wild stage presence) and Bill Bruford, who'd already established his jazzy, inventive approach to drumming as a member of Yes.

On top of that double-percussion foundation, Fripp added violinist David Cross and bassist and singer John Wetton.

Listen to 'Larks' Tongues in Aspic, Part I'

That quintet lineup quickly earned rave reviews for their highly improvised live shows. In the liner notes to the 2012 Larks' Tongues in Aspic reissue, Wetton reflected on the intensity of those early performances. "A lot of the time," he said, "the audience couldn't really tell the difference between what was formal and what wasn't because the improvising was of a fairly high standard. It was almost telepathic at times."

Capturing the magic of those shows in the studio proved problematic in the album's early recording sessions, and technical difficulties only added further strain. "Things were constantly blowing up," Wetton reflected. "We had the engineer, God bless him, who'd never done an edit before."

But those stressful sessions resulted in incredible music, from the tense, textured funkiness of "Easy Money" to the graceful, backward-masked beauty of "Book of Saturday" to the split, two-part instrumental title track, which veers from metal-tinged chromatic riffing to exotic, interlocking percussion.

That lineup wouldn't stick around long enough to record another album. Burned out from a grueling tour schedule, Muir soon departed the band in pursuit of spiritual enlightenment. The remaining quartet released 1974's Starless and Bible Black, and Fripp whittled the band down to a trio (along with Bruford and Wetton) for the raw, bone-rattling Red later that year, marking a whole new chapter of prog-rock brilliance.

Top 50 Progressive Rock Albums

More From 99.1 The Whale